Contemporary view of where the Gulf of Mexico and Colorado River meet. Visualizing the movement of the water, the breadth of the waterways, and the height of the tide contribute to the larger history of how slavery actually happened, particularly in Matagorda. Photo taken in May, 2016.

Located in the Southeastern part of the state, the Port of Matagorda offers several historical and contemporary images of the sea. From this point, looking into the Gulf of Mexico, a vast ocean leading south to the Caribbean and west to Mexico leaves viewers with a large body of water as far as the eyes can see. Today, this is a place rich with all kinds of fish, including kingfish, Spanish mackerel, blue marlin, sharks, and red snapper. History tells us that more than fish attracted a wide variety of people to this area. In fact, early nineteenth century visitors claimed that there was “no healthier region in the world” because of the alluvial soil and proximity to the water. Not surprisingly, the Matagorda seascape represents the convergence of the Colorado River with the Gulf of Mexico.

People

Texas had about 5,000 enslaved people at the time of the revolution in 1836. By 1845, when the state was annexed to the United States, this population grew to 30,000. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860 enslaved laborers was about 30% of the state’s population consisting of 182,566. In the early nineteenth century Matagorda was third to Wharton and Brazoria counties in terms of the size of the local enslaved population. These numbers represent a significant population growth, one that was all too familiar to the enslaved people on James W. Stewart’s ship, the St. Paul. This schooner carried goods that included fifty-eight human cargo from New Orleans to Matagorda County in December 1846. Stewart, identified in records as both a planter and a dentist, was born in Virginia around 1810 and likely came to Matagorda at least as early as 1845. Just five years later, his real estate was valued at $20,000. Although precisely how much of that wealth was based on his enslaved property remains unknown, the fact that 20 of the 58 individuals he transported to Matagorda were ten years old or younger suggests that he was interested in building a long-term labor force that would continue to generate income for years to come. Stewart never realized such goals as he died on September 13th, 1850.

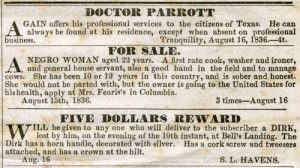

A series of newspaper ads, including one for the sale of an enslaved woman. Taken from the August 16th, 1838 edition of the Houston newspaper Telegraph and Texas Register. Like the enslaved individuals on the St. Paul, the experience of this unnamed woman must be imagined by reading between the lines. Telegraph and Texas Register, August 16, 1838, Texas Newspaper Collection, di_07393, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Used with permission.

Yet what happened to the enslaved individuals brought to Matagorda on the St. Paul? How was Willis’s experience as the oldest person on board (age 76) different from those of Susan and Lara, the youngest aboard not listed explicitly with their mother(s) (both age 2)? How did the 32 men/boys and 26 women/girls understand the forced movement from one major port city to another? By contextualizing not only the physical terrain of the Matagorda region but also the waterways that connect the area to other shores, it is possible to consider how the individuals aboard many ships like the St. Paul made sense of their arrival on new land. Did Hannah’s infant or Rose’s baby cry out during the journey? Did the sight of the Colorado River invoke fear or relief, perhaps a mixture of both, for the enslaved? While we cannot answer these questions with certainty, literally standing at the intersection of the Gulf of Mexico and the Colorado helps concretize the enslaved experience in southeastern Texas in a way that no archival document can adequately explain.

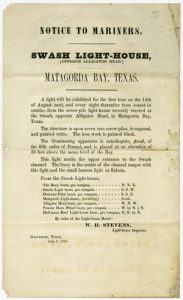

Printed notice announcing the installation of a lighthouse for Matagorda Bay near Saluria, Texas. Dated July 8, 1858. Broadside Collection, BC_0433, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Used with permission.

Commerce

This region marked a popular stopping point from trade from the Gulf South cities such as Mobile, Alabama and New Orleans, Louisiana. In addition to the fishing industry, Matagorda County was one of the largest producers of rice, sugar, and cotton in the state. Because of its location, the bay was an important trade route for both raw and processed materials to enter and exit southeast Texas.

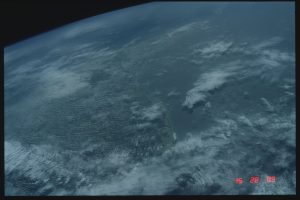

Taken in 1982, more than two hundred years after records noting Matagorda’s agricultural and strategic significance appear in Spanish, French, and English documents, this image highlights the vastness of water in the area. Shot during the space shuttle program, the image shows the Louisiana coast, Galveston Bay, and Matagorda Bay. Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The waterway connected Matagorda to international commerce trends, linking the area with the Caribbean, and, by extension, Europe, Africa, and South America. Not only did tangible goods travel along the river and the bay, but ideas, people, information, and news migrated from port to port. Indeed, Matagorda as a port city reconsiders the centrality of the region to Texas’ economic prosperity during much of the early nineteenth century.

Religion

Not far from the point of entry, one finds historic churches and religious burial grounds. Matagorda was the home to several Christian congregations such as the Baptist, Catholic, Episcopal, Methodists, and Presbyterian faiths. Some of the oldest African American churches in the state are nestled between sprawling farms along Caney Creek. This waterway has historically held religious symbolism for the residents of Matagorda, many of whom recall stories and personal anecdotes of being baptized along its banks.