View looking upstream at Caney Creek as it passes by Mt. Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church. Photo taken in May 2016.

Escaping was an active form of resistance for enslaved people in the American South, and the Matagorda region was no exception to this reality. While escape plans, routes, and destinations varied, most enslaved men and women had one trait in common: they sought to be free. Enslaved people who escaped ventured to many parts: some fled north, some fled east, and some, particularly those held in bondage in southeastern Texas, fled south, trying to reach Mexico.

People

Enslaved people who devised plans to escape likely did so by studying the terrain around and beyond where they lived. They mapped areas with high shrubbery, and down river bends, where it would be easier to hide. They often learned the hidden walkways, nooks, and thoroughfares through the marshy lowlands and high grass areas where they could pass through unseen. The Matagorda region had many such areas, particularly along Caney Creek.

Image of Ben Kinchlow.

In 1847, for example, Lizaer Moore escaped from south Texas and made her way to Mexico with her one-year-old son, Ben Kinchlow, in tow. Ben and his mother lived freely in Matamoros, Mexico until the late 1870s. Around that time, Ben decided to return to the United States, perhaps because slavery had legally ended. He came to Matagorda County, settled, and married his first wife, Christiana Temple, in a local Matagorda church.

Yet escape was not always a story that ended in freedom, however illusive that term could be for people of African descent in the American South before 1865. Evidence of branding enslaved people tells the more gruesome side of what being human chattel meant to enslavers, and how attempting to disrupt that system through running away could have physical ramifications if caught. In 1869, for example, Susan Randall’s mark of a “smooth crop off right ear, split in left,” along with a curly number “23” appear in the first volume of the Matagorda County Brand Book. Similarly, John Harrison has marks “for hogs and cattle,” explained by “the underpart of each ear sloped off.” The initials “JON” are also identified as part of his brand. How did these two individuals come to be branded? Who branded them? How did they understand these marks, particularly the numbers and initials, as they likely also saw them on animals? Did either try to run away? These kinds of questions hit hard at the daily experience of being enslaved in the Matagorda region. Historically, brands have always been used to demarcate an individual’s otherwise non-discernible property from that of another, typically in terms of cattle. Yet people have always been uniquely identifiable. Thus the question becomes: why did enslavers brand their human chattel?

Commerce

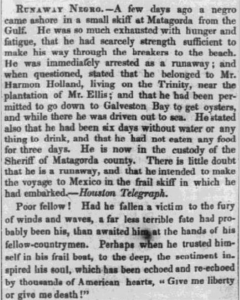

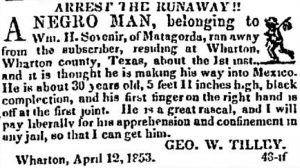

Enslaved people sought freedom and constantly engaged in running away from bondage. This was no different in the southeast Texas region, particularly the Matagorda area. Runaways created great financial losses for enslavers, who, not surprisingly, went to great lengths to try to get their laborers back, even if that implied having to spend large amounts of money issuing advertisements and offering rewards. For instance, William H. Sovenir struggled to keep enslaved people from absconding from his south Texas plantation, as demonstrated from an advertisement he paid to publish on April 12, 1853. He plead to the authorities to “ARREST THE RUNAWAY!!” who had just fled from him. The costs pertaining to loss of property when enslaved individuals escaped was high. Enslavers knew in order to recoup some of the costs they’d have to offer hefty rewards, and so often offered higher rewards the farther their escaped runaways were caught.

Newspaper advertisement concerning an enslaved man.

Religion

1853 Newspaper advertisement concerning a runaway enslaved man.

Enslaved individuals who planned to escaped bondage and those who managed to do so likely devised plans with the aid of fellow bondspeople in their communities and vicinity. These plans were devised perhaps during the few hours they were allowed to congregate for church services. Although Mt. Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church was not officially formed until 1885, it grew out of a deep religious tradition started by the county’s enslaved population. Religion served not only the needs of the white population of Matagorda, but also those of the African Americans. Enslaved individuals, like those on the Warren plantation, took whatever time their enslavers permitted for religious training to socialize with one another, travel to other plantations, and stay abreast of local happenings. Indeed, the notion of black preachers and evangelizers was a constant fear throughout the nineteenth century American South because he typically represented a respected community figure, a potentially literate bondsman (supposedly a contradiction in itself), and an authority whose influence could make or break the social standards of the given region.